This was the next step in the evolution because he sat there and said, 'Well, this is different.' The fact that it worked intrigued him, and when he showed his Mom, she asked, 'Lester, when have you ever seen a cowboy on a horse playing a railroad track?' Knowing Mother was right again, he started stuffing an acoustic guitar with shorts, t-shirts, socks, and anything he could find to deaden the response. That did something, but more was needed. Then he went to the next step, which was plaster of Paris, and he put that in his guitar, which was even better, but it didn't quite make it." The crazed vision of Les Paul pouring plaster into his guitar shows how feverishly dedicated he was to developing a solid-body guitar.

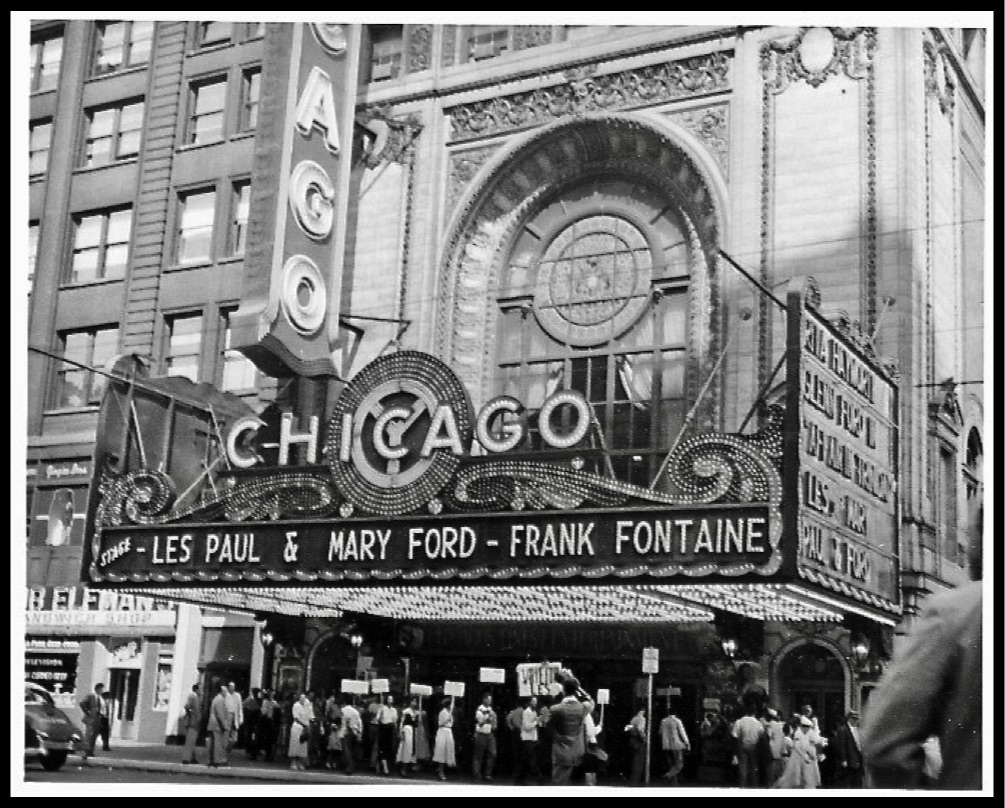

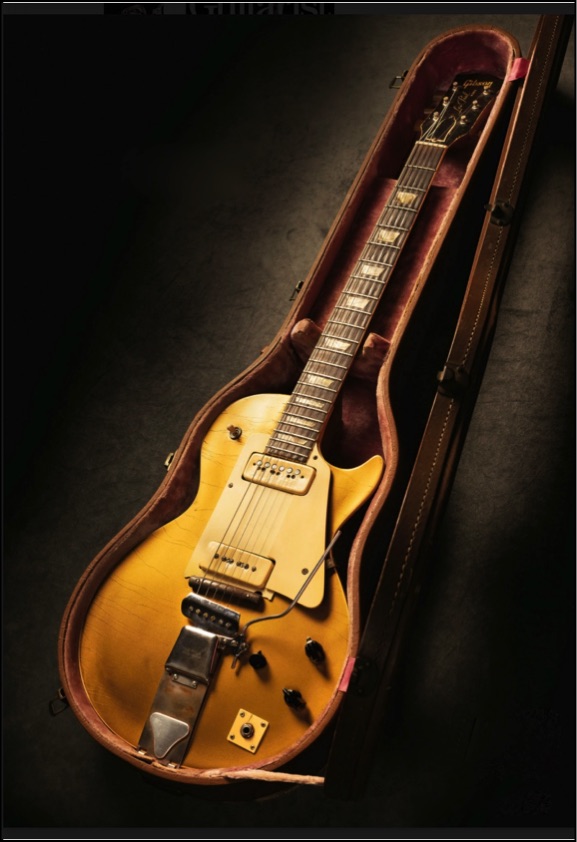

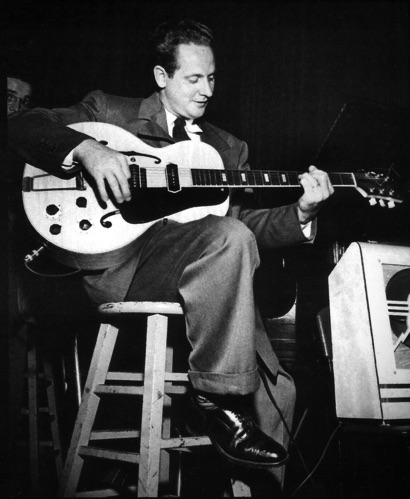

However, it took until 1938 for Les to find the ideal laboratory for his experiments on the electric guitar. "Les had moved to New York by this point," Gene explained, "and was looking for a workshop where he could build his dream instrument." Handily, he came across a rising guitar maker willing to let him use his premises. "Epiphone was in New York then, and they had a shop. Les talked his way into it and made friends with everybody," Gene recalls. "Les started working with a four-by-four plank of wood, which became the guitar he called 'The Log.'

That was another turning point in his life because that was the first time he found something that didn't weigh a ton but did provide what he was looking for in his solid platform. So he put a neck and his strings on it. By then, they had some pickups going, and he used those, too." With this crude but functional prototype up and running, Les decided to take 'The Log' out to a gig - and there, he discovered something about guitar design that had held true from 1938 to the present day. "He took 'The Log,' went to a nightclub, and played, and nobody responded," Gene recalls. "So he returned to the house, and Mom was there and asked him what happened. She was expecting a great response, but he said, 'It didn't go well...they didn't respond.'

But with his usual persistence, I mean this guy was never defeated... the cup was always half full. So he said, 'Well, maybe it has to look like a guitar?' So he went back to Epiphone and put the wings on it," Gene says, adding two curving sections of wood attached to the central plank to lend 'The Log' a regular jazz guitar outline. "They didn't change the sound at all," Gene explains. "They just made it look like a guitar. So then he returned to the same club, the same song, performed it again, and went home that night. Mom asked him again, and he said 'it was great.' She was so happy, and he was amazed by it. He said to her, 'I think I learned something tonight.' What's that, she asked? And he said, 'I think they hear with their eyes....'"

Now that 'The Log' had proven itself at its first gig, he could continue his work on perfecting his pickups as the next stage of his creation. Les decided the time was right to approach a major guitar maker. And he chose Gibson.